The initiation of the Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures (TCFD) by the Financial Stability Board (FSB) in December 2015 (Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures, 2017) represented a significant industry-led move to foster climate-related disclosures that would inform decisions in investments, lending, and insurance underwriting processes. The objective was to provide stakeholders with a more transparent view of carbon asset concentrations and the financial sector’s vulnerability to climate change risks. Access to reliable data is the starting point for addressing climate change. Accurate data is critical for assessing the influence of central banks on the climate and understanding the associated risks. This essential information paves the way for central banks to implement meaningful and practical actions.

The reporting by central banks offers detailed insights into the carbon footprint and climate-related risks tied to the assets managed by the European Central Bank (ECB) and the national central banks of the euro area, collectively referred to as the Eurosystem. This improved transparency facilitates a more nuanced understanding of their portfolios’ impact on the climate, thereby enhancing the decision-making process concerning the climate goals of central banks and aiding others in comprehending climate-related risks and impacts.

Beginning in 2023, the European Central Bank (ECB) and the Eurosystem central banks have pledged to release climate-related financial disclosures annually. These disclosures demonstrate their initiatives to reduce carbon emissions from their portfolios following the objectives set by the Paris Agreement. Additionally, these disclosures act as instruments to track their advancement and guide any required modifications to their strategies.

Eurosystem central banks’ initiatives significantly enhance openness and responsibility in how financial institutions manage and disclose climate risks. Concentrating on non-monetary policy portfolios is crucial, given their significant potential environmental impact. The yearly frequency of these disclosures enables continuous oversight and adaptation, addressing the dynamic nature of climate-related challenges and policy goals. This movement is part of a broader global shift towards incorporating environmental factors into the financial industry, aligning with international frameworks such as the Paris Agreement.

The Task Force’s guidelines are organized into four key themes representing fundamental aspects of organizational operations—governance, strategy, risk management, metrics, and targets.

This research aims to evaluate how central banks disclose governance and metrics based on TCFD recommendations.

Key Findings

- The governance part in disclosure about climate risk is fragile, with no precise frequency for reporting to the Board.

- There is no transparent monitoring system for climate-related issues.

- The best governance disclosure practices are identified in Malta, France, and Germany.

- Central banks tend to report minimum metrics to assess climate-related risks and opportunities.

- Most metrics of climate issues are explained in the central banks of France and Germany reports.

Detailed Analysis

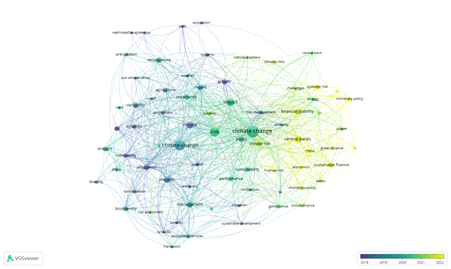

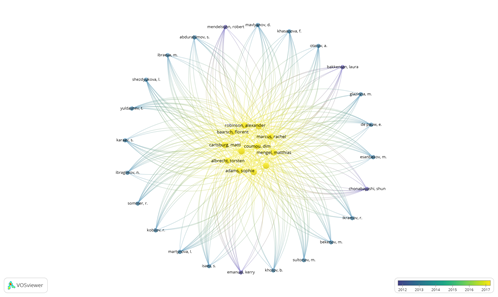

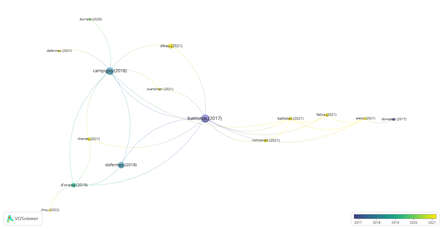

This analysis includes a literature review and a case study of 20 euro area central banks. Climate risks in central banking are very relevant in academics and practice. Firstly, this research uses a literature review based on bibliometric analysis using the Web of Science Core Collection. Based on research results for keywords: “climate risk, central bank,” 342 documents have been found. A software tool VOSviewer, was used for constructing and visualizing bibliometric networks.

In Figure 1 co-occurrence of keywords represents the frequency with which specific terms appear together in Web of Science Core Collection documents. This analysis shows that in the topic of climate risk in central banking climate change concept plays a key role. At the same time, from a time line perspective, climate risk issues are becoming more relevant in monetary policy and financial stability areas. Governance in climate risk is not a new topic, but we still see a lack of research for climate risk disclosure challenges.

Figure 2 shows the most cited authors in the field of climate risk in central banking and their cooperation. Those who had no connections in the network were eliminated. The most cited author who has no connections in the network was Dafermos Yannis, who, together with other colleagues, focused on climate risks and financial stability (Battiston, Dafermos, and Monasterolo 2021).

In Figure 3, we can see the most cited articles about climate risk in central banking. Campiglio et al. (2018) have analyzed the climate change challenges for central banks. Battiston et al. (2017) focused on the climate stress test of the financial system. Chenet, Ryan-Collins, and van Lerven (2021) investigated climate-related financial risks and discussed different approaches to financial policy. Fatica, Panzica, and Rancan (2021) analyzed the pricing of green bonds at the financial institutions level. The topic of climate risk and financial stability was analyzed by Roncoroni et al. (2021). Dikau and Volz (2021) researched central bank mandates, sustainability objectives, and the promotion of green finance. However, there is no research on climate-related information disclosure among these most cited articles.

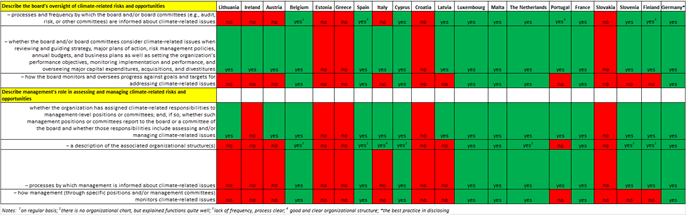

In this research, 20 central banks of the euro area were analyzed in order to identify how these central banks disclose climate-related information based on TCFD recommendations for governance and metrics.

Figure 4 presents the analysis of 20 euro area central banks’ reports on sustainable investments and climate-related risks. The results show that reports are not very transparent, as we see a lot of information that central banks do not disclose.

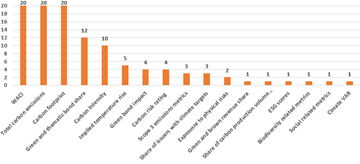

In Figure 5 are the results of metrics discloused by euro area central banks. The required metrics are only three: weighted average carbon intensity (WACI), total carbon emissions, and carbon footprint. Two extra metrics are disclosed in half of all central banks: green and thematic bond share and carbon intensity.

Other measures are disclosed only in some banks. From the reports it was clear that central banks tend to disclose more metrics next year, so the results for 2023 can be better with more efforts for disclosing information.

Implications for Businesses

The main recommendation for central banks would be to report more transparent disclosures in governance, focusing on TCFD recommendations. Processes and frequency by which the board and/or board committees (e.g., audit, risk, or other committees) are informed about climate-related issues are very important to ensure the right climate risk management in the organization. The other aspect for central banks is to have a clear monitoring of climate related issues system.

The other recommendation is to include more measures than the minimum in disclosing climate-related risks and opportunities and present it clearly by explaining the calculation and targets for the future.

Conclusions

- After analysing 20 central banks‘ climate-related financial disclosure reports, it can be concluded that euro area central banks do not disclose transparent processes by which the bank boards are informed about climate-related issues. The other important point is that most central banks do not identify the reporting frequency.

- Monitoring climate-related issues for central banks is essential, and if the central banks have no transparent processes, they can face difficulties in managing climate risk and adding value to sustainable development.In climate-related financial disclosure reports, central banks explain how the board supervises and manages risks and opportunities related to climate change. At the same time, it outlines how management evaluates and handles risks and opportunities associated with climate change. Small central banks based on foreign reserves portfolios tend to make concise reports about governance without profound explanation.

- Central banks, from 2023, have to disclose metrics by which they assess climate-related risks and opportunities. The research has shown that most central banks tend to disclose only metrics based on minimum requirements (WACI, Total carbon emissions, Carbon footprint), especially small central banks. By disclosing other metrics, there is no transparent system of providing information.

References

- Battiston, Stefano et al. 2017. “A Climate Stress-Test of the Financial System.” Nature Climate Change 7(4): 283–88.

- Battiston, Stefano, Yannis Dafermos, and Irene Monasterolo. 2021. “Climate Risks and Financial Stability.” Journal of Financial Stability 54.

- Campiglio, Emanuele et al. 2018. “Climate Change Challenges for Central Banks and Financial Regulators.” Nature Climate Change 8(6): 462–68.

- Chenet, Hugues, Josh Ryan-Collins, and Frank van Lerven. 2021. “Finance, Climate-Change and Radical Uncertainty: Towards a Precautionary Approach to Financial Policy.” Ecological Economics 183: 106957. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2021.106957.

- Dikau, Simon, and Ulrich Volz. 2021. “Central Bank Mandates, Sustainability Objectives and the Promotion of Green Finance.” Ecological Economics 184(February): 107022. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2021.107022.

- Fatica, Serena, Roberto Panzica, and Michela Rancan. 2021. “The Pricing of Green Bonds: Are Financial Institutions Special?” Journal of Financial Stability 54: 100873. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfs.2021.100873.

- Roncoroni, Alan, Stefano Battiston, Luis On, and Escobar Farf. 2021. “Climate Risk and Financial Stability in the Network of Banks and Investment Funds ∗.” SSRN Electronic Journal: 1–60.

- Task force on climate related financial disclosures. 2017. Recommendations of the Task Force on Climate-Related Financial Disclosures.