According to the European Environmental Bureau (EEB), 75% of products currently on the EU market make an implicit or explicit eco-claim, but more than half of these claims are unclear, misleading, or unjustified. Climate neutrality claims are among the most misleading green claims on the market. Almost half of the 230 eco-labels in use in the EU have very weak or no verification procedures (European Commission, 2023). This situation can cause various negative emotions among consumers, including mistrust, confusion, skepticism, and unwillingness to purchase sustainable products.

Keywords

Introduction

Research indicates that 60% of consumers worldwide consider sustainability a crucial purchasing criterion, and 66% are willing to pay more for sustainable products (Netto et al., 2020; Volschenk et al., 2022). However, many companies imitate sustainable practices without genuinely implementing them—a phenomenon known as greenwashing. Greenwashing involves misleading communication that exaggerates the environmental benefits of a company’s actions or products (Huang et al., 2025; Shojaei et al., 2024). According to Szabo and Webster (2021), greenwashing can be perceived or non-perceived. In perceived cases, consumers recognize the company’s claims as deceptive; in non-perceived instances, they believe the company’s marketing and view it as sustainable when it is not. De Ferrer (2020) identifies two main reasons for greenwashing: large corporations often attempt to conceal their poor environmental performance through grand “green” gestures, and many companies use terms like “green,” “sustainable,” “organic,” or “vegan” superficially to attract consumers. Greenwashing generates negative emotions such as distrust, scepticism, confusion, and reduced loyalty. Ahmad and Zhang (2020) argue that it fosters a sceptical societal attitude toward environmental protection. The growing prevalence of misleading green claims increases uncertainty about the credibility of corporate environmental communication, weakening consumer trust and complicating purchasing decisions (Thogersen, 2021; Zhang et al., 2018). Consequently, greenwashing is negatively linked to consumers’ purchase intentions (Huang et al., 2025; Zhou et al., 2022). Misled consumers also struggle to accurately interpret and evaluate product information. Chen et al. (2019) warn that excessive and unverified sustainability claims may render sustainability irrelevant in consumers’ choices, leading to societal indifference. Ultimately, greenwashing undermines confidence in corporate environmental performance, promoting widespread cynicism and distrust (Tri Ha et al., 2019; Martínez et al., 2020).

This study aims to determine the impact of imitation sustainability claims on consumers’ purchasing decisions.

The chosen empirical research methodology employed a quantitative approach through a questionnaire survey. Data analysis was conducted using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) alongside descriptive statistical methods.

Key Findings.

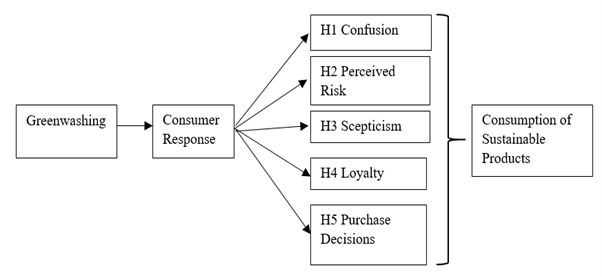

The empirical research findings demonstrate the predominantly negative impact of greenwashing on consumers. This causes confusion among consumers, increases perceived risk, fosters mistrust in the company and its products, and may gradually lead to skepticism, which may result in sustainable consumption practices being overlooked. Moreover, greenwashing diminishes consumer loyalty, significantly influencing their decision-making processes and their willingness to purchase sustainable products.

Detailed Analysis.

The quantitative research method chosen for the empirical study was a questionnaire survey. The survey data were collected from Lithuanian consumers (250 respondents) through a random purposive sampling method. The questionnaire has a high level of content validity (Cronbach’s alpha (α) value is 0.78) and was designed to accept or reject five hypotheses. Figure 1 provides the research model.

Relationships between variables were analysed using Sig. (2-tailed) and Pearson Correlation. A correlation is significant when Sig. (2-tailed) <.001; values between 0.5–1 indicate a strong correlation, 0.3–0.49 a medium one, and <0.29 a low correlation. The findings show that consumers prioritise sustainable products (Sig. (2-tailed) <.001, Pearson Correlation .805) over a sustainable corporate image or initiatives (Sig. (2-tailed) <.012, Pearson Correlation .223). Advertising motivates 23% of respondents to buy sustainable products, while 24% purchase them randomly. This incidental behaviour may indicate the influence of greenwashing through colours, natural imagery, or eco-associated packaging.

Almost half (45%) of respondents decide whether a product is sustainable based on product label descriptions, 23% trust advertising, 19% rely on packaging, and 13% examine claimed certificates. Females tend to trust advertising and packaging more, while males rely on product descriptions and certificates (Sig. (2-tailed) <.001, Pearson Correlation .376).

Although 73% of respondents are aware of greenwashing, only 7% can recognise it when it involves colours or images, and 26% stated they had never experienced it. A strong correlation was observed between those unaware of greenwashing and those who had not encountered it (Sig. (2-tailed) <.001, Pearson Correlation .628). This suggests that individuals unfamiliar with greenwashing fail to recognise it in practice, leaving their purchasing decisions unaffected. The difficulty of proving intentional deception through associative marketing supports this finding.

A strong correlation also emerged between product distrust and the importance placed on sustainability (Sig. (2-tailed) <.001, Pearson Correlation .806), implying that environmentally conscious consumers tend to distrust products due to greenwashing. For 24% of respondents, greenwashing induces scepticism; however, it does not undermine belief in sustainability overall (no correlation found; Sig. (2-tailed) .016, Pearson Correlation .196). Thus, consumers remain supportive of sustainability principles despite manipulative marketing. Finally, 65% of respondents reported they would not purchase a product if they recognised it as greenwashing. Overall, the study results indicate that only one of the five hypotheses (H3) was rejected.

Implications for Businesses.

The findings of the study can contribute to more effective marketing strategies for businesses and better policies for regulators to protect consumers from misleading practices. For companies, this could provide an opportunity to highlight the importance of sincere efforts to achieve sustainability and transparent communication to secure consumer trust and loyalty. Policymakers could use the insights to strengthen regulation and enforcement mechanisms to effectively combat greenwashing. In addition, consumers could benefit from better awareness and education on greenwashing tactics to make more informed purchasing decisions and support true sustainable products and businesses.

Conclusion.

The study contributes to the scientific literature by providing empirical evidence on the specific aspects in which greenwashing influences consumer decision-making. Understanding the impact of greenwashing on consumer decisions is crucial for both researchers and practitioners. The study contributes to clarifying the extent to which greenwashing undermines trust in brands, influences purchase decisions, and affects consumer perceptions of sustainability.

References

- Ahmad, W., Zhang, Q. (2020). Green purchase intention: Effects of electronic service quality and customer green psychology. Journal of Cleaner Production, 267, 122053. DOI: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.122053

- Chen, H., Bernard S. & Rahman, I. (2019). Greenwashing in hotels: A structural model of trust and behavioral intentions. Journal of Cleaner Production, 206 (1), 326– 335. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2018.09.168

- De Ferrer, M. (2020). What Is Greenwashing and Why Is It a Problem? Euronews. [Accessed 20.02.2024]. Available from Internet: https://www.euronews.com/green/2020/09/09/what-is-greenwashing-and-why-is-it-a-problem

- De Freitas Netto, S. V., Sobral, M. F. F., Ribeiro, A. R. B., & da Luz Soares, G. R. (2020). Concepts and forms of greenwashing: A systematic review. Environmental Sciences Europe, 32(1), 1-12. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12302-020-0300-3

- European Commission. Energy, Climate Change, Environment. (2023). Green Claims. [Accessed 09.03.2024]. Available from Internet: https://environment.ec.europa.eu/topics/circular-economy/green-claims_en

- Huang, Z., Shi, Y., & Jia, M. (2025). Greenwashing: A systematic literature review. Accounting and Finance (Parkville), 65(1), 857–882. https://doi.org/10.1111/acfi.13352

- Martínez, M., Cremasco, C., Filho, G., Almeida L. R., Junior, S. et al. (2020). Fuzzy inference system to study the behavior of the green consumer facing the perception of greenwashing. Journal of Cleaner Production. 242 (3), 116064. DOI:10.1016/j.jclepro.2019.03.060

- Shojaei, A. S., Barbosa, B., Oliveira, Z., & Coelho, A. M. R. (2024). Perceived greenwashing and its impact on eco-friendly product purchase. Tourism & Management Studies, 20(2), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.18089/tms.20240201

- Szabo, S. & Webster, J. (2021). Perceived Greenwashing: The Effects of Green Marketing on Environmental and Product Perceptions, Journal of Business Ethics. 171 (4) 719-739. DOI:10.1007/s10551-020-04461-0

- Tri Ha, M., Ngan, V. T. K., Nguyen, N. D. (2022). Greenwash and green brand equity: The mediating role of green brand image, green satisfaction and green trust and the moderating role of information and knowledge. Business Ethics, the Environment & Responsibility. 31 (4) 904-922. DOI: 10.1111/beer.12462

- Thogersen, J. (2021). Consumer behavior and climate change: Consumers need considerable assistance. Current Opinion in Behavioral Sciences, (42), 9–14. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cobeha.2021.02.008

- Volschenk, J., Gerber, C., Santos, B. A. (2022). The (in)ability of consumers to perceive greenwashing and its influence on purchase intent and willingness to pay. South African Journal of Economic and Management Sciences, 25 (1), 4553. DOI 10.4102/sajems.v25i1.4553

- Zhang L, Li D, Cao C, Huang S (2018). The influence of greenwashing perception on green purchasing intentions: the mediating role of green word-of-mouth and moderating role of green concern. Journal of Cleaner Production, 187, 740–750. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2018.03.201

- Zhou, C., Xia, W., Feng, T., Jiang, J. (2022). Enabling environmental innovation via green supply chain integration: A perspective of information processing theory. Australian Journal of Management, 48 (2), 235–261. https://doi.org/10.1177/03128962221092089